Select a category

Advertisement

London Bridge, The PRIDE Of LONDON

4 years ago

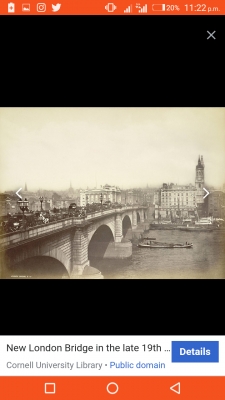

Several bridges named London Bridge have spanned the River Thames between the City of London and Southwark, in central London. The current crossing, which opened to traffic in 1973, is a box girder bridge built from concrete and steel. It replaced a 19th-century stone-arched bridge, which in turn superseded a 600-year-old stone-built medieval structure. This was preceded by a succession of timber bridges, the first of which was built by the Roman founders of London.

London Bridge | |

|---|---|

London Bridge in December 2015 | |

| Coordinates | 51°30′29″N 0°05′16″W |

| Carries | Five lanes of the A3 |

| Crosses | River Thames |

| Locale | Central London |

| Maintained by | Bridge House Estates, City of London Corporation |

| Preceded by | Cannon Street Railway Bridge |

| Followed by | Tower Bridge |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Prestressed concrete box girder bridge |

| Total length | 269 m (882.5 ft) |

| Width | 32 m (105.0 ft) |

| Longest span | 104 m (341.2 ft) |

| Clearance below | 8.9 m (29.2 ft) |

| Design life | Modern bridge (1971–present) Victorian stone arch (1832–1968) Medieval stone arch (1176–1832) Various wooden bridges (AD 50–1176) |

| History | |

| Opened | 17 March 1973; 47 years ago |

Wikimedia | © OpenStreetMap | |

The current bridge stands at the western end of the Pool of London and is positioned 30 metres (98 ft) upstream from previous alignments.

Advertisement

Advertisement

The modern bridge is owned and maintained by Bridge House Estates, an independent charity of medieval origin overseen by the City of London Corporation. It carries the A3 road, which is maintained by the Greater London Authority.[1] The crossing also delineates an area along the southern bank of the River Thames, between London Bridge and Tower Bridge, that has been designated as a business improvement district.[2]

The bridge area has twice been the target of terrorist attacks - once in 2017, and again in 2019.

HistoryEdit

LocationEdit

The abutments of modern London Bridge rest several metres above natural embankments of gravel, sand and clay. From the late Neolithic era the southern embankment formed a natural causeway above the surrounding swamp and marsh of the river's estuary; the northern ascended to higher ground at the present site of Cornhill. Between the embankments, the River Thames could have been crossed by ford when the tide was low, or ferry when it was high. Both embankments, particularly the northern, would have offered stable beachheads for boat traffic up and downstream – the Thames and its estuary were a major inland and Continental trade route from at least the 9th century BC.[3]

There is archaeological evidence for scattered Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age settlement nearby, but until a bridge was built there, London did not exist.[4] A few miles upstream, beyond the river's upper tidal reach, two ancient fords were in use.

Advertisement

Roman bridgesEdit

The first bridge was probably a Roman military pontoon type, giving a rapid overland shortcut to Camulodunum from the southern and Kentish ports, along the Roman roads of Stane Street and Watling Street (now the A2). Around AD 50, the temporary bridge over the Thames was replaced by a permanent timber piled bridge, maintained and guarded by a small garrison. On the relatively high, dry ground at the northern end of the bridge, a small, opportunistic trading and shipping settlement took root and grew into the town of Londinium.[6] A smaller settlement developed at the southern end of the bridge, in the area now known as Southwark. The bridge was probably destroyed along with the town in the Boudican revolt (AD 60), but both were rebuilt and Londinium became the administrative and mercantile capital of Roman Britain.

Advertisement

Early medieval bridgesEdit

With the end of Roman rule in Britain in the early 5th century, Londinium was gradually abandoned and the bridge fell into disrepair. In the Anglo-Saxon period, the river became a boundary between the emergent, mutually hostile kingdoms of Mercia and Wessex. By the late 9th century, Danish invasions prompted at least a partial reoccupation of the site by the Saxons. The bridge may have been rebuilt by Alfred the Great soon after the Battle of Edington as part of Alfred's redevelopment of the area in his system of burhs,[9] or it may have been rebuilt around 990 under the Saxon king Æthelred the Unready to hasten his troop movements against Sweyn Forkbeard, father of Cnut the Great. A skaldic tradition describes the bridge's destruction in 1014 by Æthelred's ally Olaf,[10] to divide the Danish forces who held both the walled City of London and Southwark. The earliest contemporary written reference to a Saxon bridge is c.1016 when chroniclers mention how Cnut's ships bypassed the crossing, during his war to regain the throne from Edmund Ironside (see Battle of Brentford (1016)).

Following the Norman conquest in 1066, King William I rebuilt the bridge. The London tornado of 1091 destroyed it, also damaging St Mary-le-Bow.[11] It was repaired or replaced by King William II, destroyed by fire in 1136, and rebuilt in the reign of Stephen. Henry II created a monastic guild, the "Brethren of the Bridge", to oversee all work on London Bridge.

Advertisement

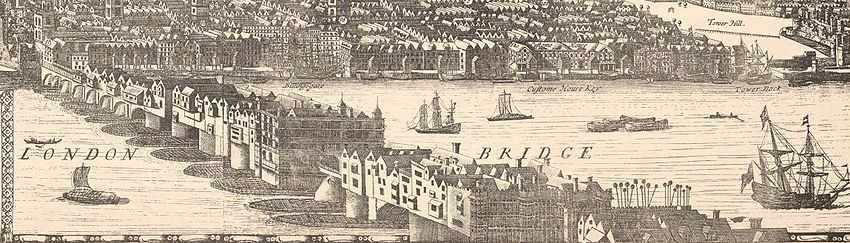

"Old" London Bridge (1209–1831)Edit

After the murder of his former friend and later opponent Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury, the penitent King Henry II commissioned a new stone bridge in place of the old, with a chapel at its centre dedicated to Becket as martyr. The archbishop had been a native Londoner and a popular figure. The Chapel of St Thomas on the Bridge became the official start of pilgrimage to his Canterbury shrine; it was grander than some town parish churches, and had an additional river-level entrance for fishermen and ferrymen.

Advertisement

The bridge was 26 feet (8 m) wide according to some records that were later disputed.[14][15] The structure was about 800–900 feet (240–270 m) long, supported by 19 irregularly spaced arches, founded on starlings set into the river-bed. It had a drawbridge to allow for the passage of tall ships, and defensive gatehouses at both ends. By 1358 it was already crowded with 138 shops. At least one two-entranced, multi-seated public latrine overhung the bridge parapets and discharged into the river below; so did an unknown number of private latrines reserved for Bridge householders or shopkeepers and bridge officials. In 1382–83 a new latrine was made (or an old one replaced) at considerable cost, at the northern end of the bridge.[16]

The buildings on London Bridge were a major fire hazard and increased the load on its arches, several of which had to be rebuilt over the centuries. In 1212, perhaps the greatest of the early fires of London broke out on both ends of the bridge simultaneously, trapping many people in the middle.

Advertisement

By the Tudor period, there were some 200 buildings on the bridge. Some stood up to seven storeys high, some overhung the river by 7 feet (2.1 m), and some overhung the road, to form a dark tunnel through which all traffic had to pass; this did not prevent the addition, in 1577, of the palatial Nonsuch House to the buildings that crowded the bridge. The available roadway was just 12 feet (4 m) wide, divided into two lanes, so that in each direction, carts, wagons, coaches and pedestrians shared a single file lane 6 feet (1.8 m) wide. When the bridge was congested, crossing it could take up to an hour. Those who could afford the fare might prefer to cross by ferry, but the bridge structure had several undesirable effects on river traffic. The narrow arches and wide pier bases restricted the river's tidal ebb and flow, so that in hard winters, the river upstream of the bridge became more susceptible to freezing and impassable by boat. The flow was further obstructed in the 16th century by waterwheels (designed by Peter Morice) installed under the two north arches to drive water pumps, and under the two south arches to power grain mills; the difference in water levels on the two sides of the bridge could be as much as 6 feet (1.8 m), producing ferocious rapids between the piers resembling a weir.[17] Only the brave or foolhardy attempted to "shoot the bridge"-steer a boat between the starlings when in flood-and some were drowned in the attempt.

Advertisement

The southern gatehouse became the scene of one of London's most notorious sights - a display of the severed heads of traitors, impaled on pikes[19] and dipped in tar and boiled to preserve them against the elements. The head of William Wallace was the first to appear on the gate, in 1305, starting a tradition that was to continue for another 355 years. Other famous heads on pikes included those of Jack Cade in 1450, Thomas More in 1535, Bishop John Fisher in the same year, and Thomas Cromwell in 1540. In 1598, a German visitor to London, Paul Hentzner, counted over 30 heads on the bridge:[20]

On the south is a bridge of stone eight hundred feet in length, of wonderful work; it is supported upon twenty piers of square stone, sixty feet high and thirty broad, joined by arches of about twenty feet diameter. The whole is covered on each side with houses so disposed as to have the appearance of a continued street, not at all of a bridge. Upon this is built a tower, on whose top the heads of such as have been executed for high treason are placed on iron spikes: we counted above thirty.

Evelyn's Diary noted that the practice stopped in 1660, following the Restoration of King Charles II,[21] although heads continued to be displayed at Temple Bar, about half a mile north west, as late as 1772.[22] In 1666, the Great Fire of London first destroyed the bridge's waterwheels, preventing them from pumping water to fight the fire, and then burned one third of the houses on the bridge; a gap in the building left by a previous fire in 1633 prevented the destruction of the rest.[23]

Over the years, incidents of arches collapsing were recorded in 1281–82 and in 1437. A survey in 1683 provided specifics as to the bridge's dimensions, stating that it had been 15 feet (4.6 m) wide but was recently widened to 20 feet (6.1 m).[24] Considering the houses, the width actually available for traffic however, was only about 12 feet (3.7 m).[14][15]

A recently rediscovered list of leases from the 17th century provided a great deal of information, including the size and location of the 124 houses, the chapel, the gate and the drawbridge tower.[15] By 1710, most of the houses on the bridge had been rebuilt in the Restoration style and in order to widen the roadway to 20 feet (6.1 m), the new houses were built overhanging the river supported by wooden girders and struts which hid the tops of the arches.[25] In 1722 congestion was becoming so serious that the Lord Mayor decreed that "all carts, coaches and other carriages coming out of Southwark into this City do keep all along the west side of the said bridge: and all carts and coaches going out of the City do keep along the east side of the said bridge." This has been suggested as one possible origin for the practice of traffic in Britain driving on the left.[26]

A fire in September 1725 destroyed houses on the bridge's east side and damaged some on the west side; they were rebuilt.[14] The last houses to be built on the bridge were designed by George Dance the Elder in 1745,[27] but even these elegant buildings had begun to subside within a decade.[28] In 1756, the London Bridge Act gave the City Corporation the power to purchase all the properties on the bridge so that they could be demolished and the bridge improved. While this work was underway, a temporary wooden bridge was constructed to the west of London Bridge.

Advertisement

Demolition of the houses was completed in 1762 and the last tenant departed after some 550 years of housing on the bridge.[30] Under the supervision of Dance the Elder, the roadway was widened to 46 feet (14 m)[31] and a balustrade was added "in the Gothic taste" together with fourteen stone alcoves for pedestrians to shelter in.[32] However, the creation of the Great Arch had weakened the rest of the structure and constant expensive repairs were required in the following decades; this, combined with congestion both on and under bridge, often leading to fatal accidents, resulted in public pressure for a modern replacement.[33]

Disclaimer If this post is your copyrighted property, please message this user or email us your request at [email protected] with a link to this post

Advertisement

Kuamo

Kuamo