profile/4398IMG_20200719_072934.jpg

Youngest22

Barely 24hrs After US Reportedly Opposed Her Stance, See What Ngozi Okonjiweala Said.

~1.5 mins read

Good evening guys, you are welcome to my last post for today.

Please before you continue reading, make sure to follow my account so that you will get notified whenever I have some interesting and exciting articles.

Ngozi Okonjiweala is a Nigerian born Economist and international development expert. She sits on the board of standard chartered bank, Twitter , Global Alliance for vaccines and immunization , and African Risk capacity.

Nigerians and Afticans was thrown into joy and happiness when they learnt their own person have emerged the winner of the Director of world trade organization, defeating her South Korean counterparts. However, the joy was short-lived when the United States came out to oppose it. They don't want her to head the office.

This has given a lot of people mixed feelings and reactions but what she said on Twitter this evening is a clear confirmation that she will assume the office soon.

She wrote " Happy for the success and continued progress of our @Wto DG bid. Very humbled to be declared the candidate with the largest, broadest support among members and most likely to attract consensus. We move on to the next step on November 9, despite hiccups. We are keeping the positivity going!" She said.

It looks like the results was later cancelled and the next voting scheduled to take place on 9th of November 2020.

profile/4398IMG_20200719_072934.jpg

Youngest22

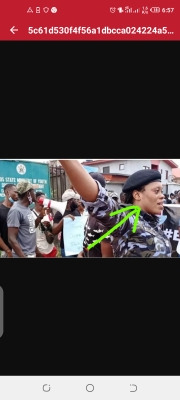

She Must Not Be Sacked, Demoted Or Punished - Omokri Warns Police For Allege Attempt To Sack Officer

~3.6 mins read

In every aspect of life, there is always an outcast. An outcast is individual who thinks differently or who holds an unpopular opinion totally different from others. For some days now, most towns and cities in this country have been faced with proliferation of civil unrest. Nigerians are simply weary of police brutalities and killings, especially from a unit of police called Special Anti-Robbery Squads (SARS).

Though it was created with a sole intent of combating crimes from criminal elements amongst our midst, SARS have since gone off the hook. Their excesses can now be heard, read or seen in the full glare of the public.

Nigerian youths in their hundreds have taken into streets in recent week to condemn in strongest terms incessant molestations, harassments, killings or maimings by SARS men. This is necessitated by unprofessional conducts displayed by this arm of security, and extrajudicial killings of Nigerians.

In some cases, our are youths are being harassed, defrauded and killed by men employed to protect the citizens. Wearing nice dress, using iPhones and laptops or driving exotic cars have now seemingly become offences, especially if you are a youth.

And just yesterday, Nigerians heaved a sigh of relief after Inspector General of Police, Adamu Muhammed made an official statement on disbandment of SARS across the country.

However, one of the police officers who lent support to the peaceful protest in Lagos is currently under threat. Her job is now online as she risks being sacked or demoted for joining the protest.

Speaking on potential threats she may face, a popular politician, Mr. Reno Omokri, has sounded a note of warning to those in authorities to desist from taking such decision to punish the officer.

His statement read: "Patricia Amadin, DPO of Anthony Police station, Lagos, who gave support to #SARSMustEnd protesters must not be sacked, demoted or punished for her heroism. We are watching. No harm must befall her. Patricia is a heroine."

Advertisement

Link socials

Matches

Loading...