Ugobaby

Lawyer : I Give Out As Much Resources As I Can

Wants to meet A Boyfriend : I Need A Change Please!

Articles

84

Followers

31

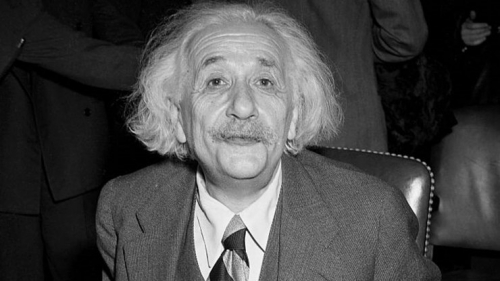

profile/4770IMG-20200918-WA0002.jpg

Ugobaby

Preparation & Carefulness Are Key Qualities Of Smart People

~3.2 mins read

The fastest way to identify intelligent people is to ask an easy question, followed by a more complex one.

Let’s say you’re in a Zoom call with your marketing team. You need ideas on how to spend the last, unallocated $5,000 of your budget. That’s a lot of money, so the ideas better be good. Whose ideas can you trust?

According to Shailesh Panthee, asking a very easy question in a group setting will reveal who’s eager — maybe too eager — to prove themselves.

For example, you could ask a basic question about marketing lingo. “Remind me again, what’s CTR stand for?” CTR means click-through-rate. It’s the percentage of people who click on an element after viewing it.

Most people in marketing know the term, and your team might think it’s a bit weird that you’re asking such a simple question in the first place. That’s okay, however, because what’s important is what happens next: Who shouts the answer the fastest and the loudest? Are multiple people on the call blurting out the answer? Do they talk over one another?

If you ask Panthee, people who engage in shouting matches over simple-to-answer questions are so desperate for brownie points that they a.) forget to consider how valuable the answer is and b.) skip fact-checking and thinking through their response. He says:

Smart people are smart enough to know that answering that question will not make them unique. They answer questions which require analytical and critical thinking rather than just recall or memory.

I’m neither a genius nor did I think a lot about positioning in high school, but as someone who raised his hand a lot, I can point to another reason why smart folks might hesitate to answer obvious questions: They suspect it’s a trap.

Whenever our English teacher asked for straight-up vocabulary translations, I was skeptical. Why did she ask us the word for “bread” again? Is she hiding a hard follow-up behind this simple opener?

If you’re on the other side of this equation, aka leading the Zoom call, that’s exactlywhat you should be doing. With the noise cleared away, you can now drop the actual, more complex, probably creative ask: How should we spend our remaining marketing budget?

Chances are, now, Overzealous Oliver and Valerie Validation-Seeker will hold their breath. They’re either content with the approval they snagged from answering the simple question or, quite frankly, stumped.

The smart ones won’t jump at you with an answer. You might even have to prompt them. Maybe, they’ll counter with a question: “Well, what’s our goal in spending the money?” Eventually, however, they will suggest an idea.

“How about we split the money five ways and run paid ads on five different platforms to determine which one we should double down on to promote our company next year?” Wow Intelligent Isaac, what hat did you pull that one from? Good job!

Smart people know that listening is more valuable than talking and that neither beats thinking for yourself. They try to avoid repeating the obvious so they can spend their time and energy on what requires analysis and creativity.

In fact, Isaac probably thought about this problem before you even brought it up. He stumbled upon it and spent a few minutes mulling it over. So when you asked him for an idea, he was ready. And yet, he was still cautious.

You’ll find this same balance of preparation and carefulness in smart people all around.

If you ask them an embarrassingly easy question in private, they won’t laugh at you. They won’t criticize you. They’ll give you the answer and not tell anyone about it.

If you ask them something more complicated, they’ll give you options, start with, “I don’t know,” or answer with a question to get more information. They’ll pause, hesitate, and never present their answer as the end-all, be-all.

Being too eager opens us to error and careless mistakes. Reserve and structured thinking won’t always stand out, but they’re always worth commending.

Ask easy questions, then follow up with hard ones. Smart people are all around us. Learning to identify them is only one part of the picture, but it’s great practice along the way of finding our own potential.

profile/4770IMG-20200918-WA0002.jpg

Ugobaby

When To Use "who" Or "whom" In A Sentence. Read To Learn.

~6.7 mins read

I stepped down from the copy department of The New Yorker almost two years ago, hanging up my parentheses and turning over the comma shaker to my successor, who I know will use it judiciously, but I still love the magazine and lose sleep when an oversight (as we prefer to call it) sneaks into its pages. Copy editors never get credit for the sentences we get right, but confuse “who†and “whom†and you are sure to be the center of attention, at least briefly. If you thought the “who†in the previous sentence should have been a “whom,†you are not alone. Let’s review.

Advertisement

Link socials

Matches

Loading...