Itoro

Psychologist : Am A Psychologist,who Offers Professional Help To Those Who Needs Psychological Assistance

Wants to meet Just Friends

Most maternal and newborn deaths are largely preventable or treatable if skilled health care is provided during the intrapartum and early postnatal periods [1]. During the immediate postpartum period, critical interventions to end preventable maternal and newborn deaths need to be delivered [2]. However, in most developing countries, postnatal care (PNC) is the least prioritized program component of maternal and child survival interventions which is illustrated by a high rate of underutilization and discontinuity of maternal and child health programs [3]. Likewise, postnatal care has been poorly implemented in Ethiopia [4]. Despite the efforts of the government and its partners to improve the use of maternal health services through expansion of primary health care, except user free of maternal health services, strengthening the community health system to provide postpartum home visits, only 17% of women received PNC during the critical period of the first 2 days after delivery; and only 1% was visited by health extension workers, frontline community health workers. Less than 2% who delivered outside of the facility and 42% who delivered at health facility received PNC within 2 days. To make matters worse, of those who delivered in the facility, most did not receive proper PNC. More than two-thirds (69%) of women who had vaginal birth at the facility were discharged within 24-h after birth and commonly discharged within 6 h of delivery [5].

Methods

Context

Ethiopia has expanded primary health care services through expansion of the Health Extension Program (HEP) and expansion of health centers and promotion of early healthcare-seeking through community mobilization to reach most communities and households and provide preventive, promotive, and basic curative services. The promise of the HEP has been the graduation of model families where health extension workers (HEWs) train households to acquire the necessary knowledge, skills, and behavior change in health practices. When these households demonstrate practical changes in the use of health service programs: environmental health, personal hygiene, and serve as models in their community, then they graduate. To reach more communities, this strategy has been accelerated through the participatory engagement of model families that are early adopters of desirable health practices and have acceptance and credibility by their community and the women development army (WDA) group. The WDA network builds on the critical mass of model families and creates volunteer leaders that scale-up the dissemination of knowledge, innovation, and service utilization through social networks. They are actively engaged in promotion and prevention activities as well as social mobilization efforts to expand HEP deeper into communities and families and ensure community ownership [20].

Low back pain (LBP) is a common musculoskeletal problem during pregnancy, with an estimated prevalence ranging from 30–78% [1, 2]. This condition is generally severe enough to interfere with daily life, causing limitations in performance and productivity at work [3]. The consequences of pregnancy-related LBP involve increased sick leave, high rates of functional disability, and increased seeking of treatment for symptom relief. However, regression of LBP after delivery may be slow and incomplete, and 15% of women with this condition have dated the commencement of pain to the time of one of their pregnancies [4]. These intractable reactions may trigger perinatal depression [5].

Methods

Design

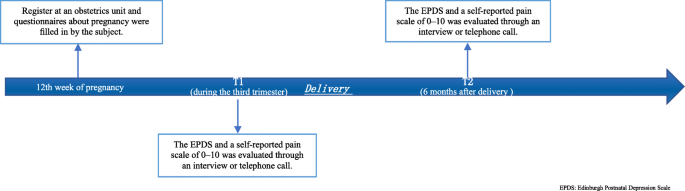

This was a retrospective case-control study conducted from January 2016 to April 2019. This research has been approved by the IRB of the authors’ affiliated institutions.

Subjects

Instruments

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)

Description of low back pain (LBP) and its subdivisions

Advertisement

Link socials

Matches